If corrosion occurs between contacts, this can cause a fire hazard. In a world with an aerosol for every problem, I would like to go back to basics.

Table of Contents

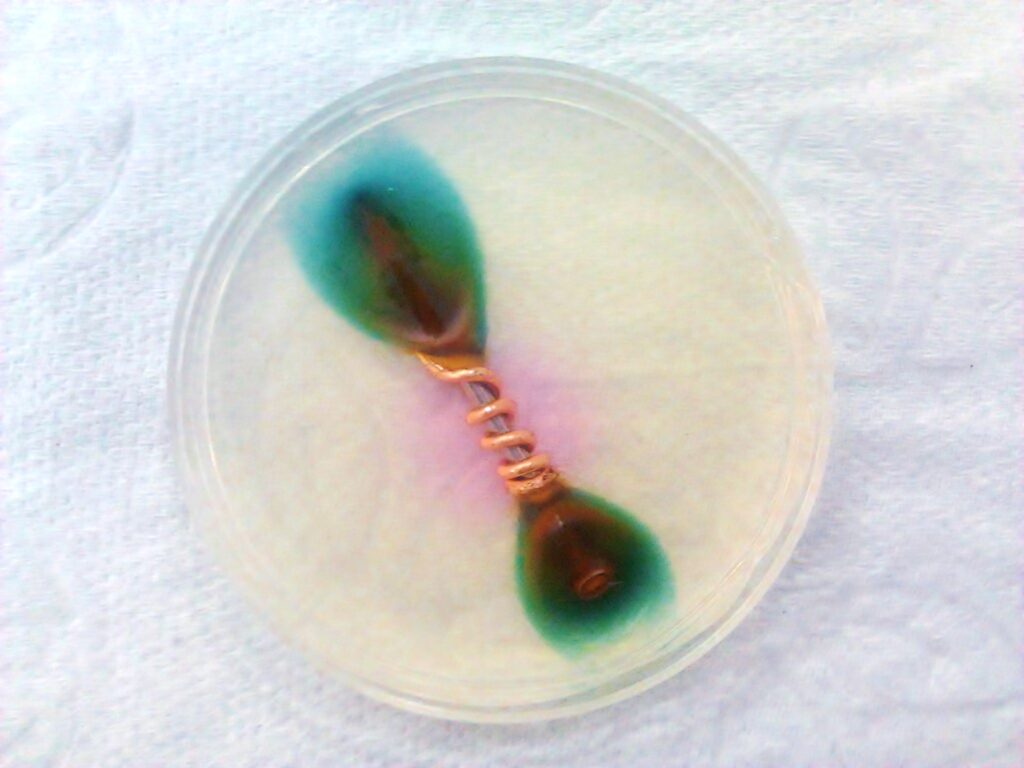

Case: Bus bars on LiFePO4 batteries

That is a good example. The battery has an aluminium head with a threaded hole and the copper connecting strip is pressed onto it with a screw.

A quote, somewhere from the sixties…

“In those days, there were only zinc-carbon batteries. If they were charged, it was all right, but if you didn’t remove them in time, you could count on a devastating electrochemical reaction at the poles. My father taught me to always apply petroleum jelly when replacing them. In the end, it saved radios, flash units, cameras, flash-lights and calculators from destruction. When alkaline batteries came onto the market, the problem disappeared. However, to this day it is not bad practice to apply petroleum jelly to the terminal connections of car batteries.”

Clean surfaces first

It is important that there is a “metal to metal connection”. Therefore, always remove oxides and dirt first by light sanding and cleaning with isopropanol.

The real contact

The tightening torque of the screw, bolt or nut determines how much pressure there is on the contact surface – you could see the thread as an extremely strong spring that presses the surfaces together.

However, under a microscope you will discover that the contact surfaces are not flat at all and look more like a microscopic mountain landscape. Where mountain peaks – so called asperities – meet, there is contact and a current can flow.

In practice, the effective contact surface is far less than one per cent of the total contact surface.

The problem becomes even more complex because, firstly, there is always some contamination present and, secondly, especially with aluminium, there is always a thin corrosion layer. For metallic contact at asperities, the pressure – the tightening torque – must be high enough for sufficient deformation.

This model results in a electrical contact resistance (ECR). If there is enough resistance and enough current, a considerable amount of heat can be produced. Always add high current contacts to your service schedule and check torques of bolts and nuts and look for corrosion.

What could possibly go wrong?

As long as no moisture or dirt can get between the contact surfaces, nothing will happen. However, the smallest drop of condensation on a cool evening will immediately penetrate the valleys by capillary action. Condensation is very pure water that is not conductive. However, some metal ions will dissolve in it and the corrosion-fest has begun.

… and how to prevent it

You can guess how to prevent it: With petroleum jelly. Petrolatum: CAS number 8009-03-8. And before you say that there are much better remedies, here are some characteristics that make petroleum jelly such a great solution:

- Petroleum jelly is inert. This means that it reacts chemically with almost nothing and retains its properties for an extremely long time. It does not become hard, crumbly or soft.

- Petroleum jelly is pH-neutral. So it will not interact with the metals of the contact surfaces.

- Petroleum jelly is flexible. It will always move along with expansion and contraction due to heat and will never have cracks through which water can penetrate.

- Petroleum jelly is cheap and widely available.

- I have not thoroughly researched other agents and they may be better in specific situations, like Noalox. However, I am convinced that petroleum jelly is almost never a wrong first choice.

Having stated that… Alternatively, you can consider using dielectric greases. These are silicon-based greases. In general, they are more resistant to higher temperatures. A word of caution, silicone greases consist of silicone oil (PDMS) and a thickener. The thickener used is variable. For example, it can consist of stearates, silica and or PTFE. Needless to say, the properties of “silicon grease” strongly depend on the type of thickener. The risk of reducing the asperity zone because of microscopic PTFE-layers – it is dielectric – keeps me far away from them.